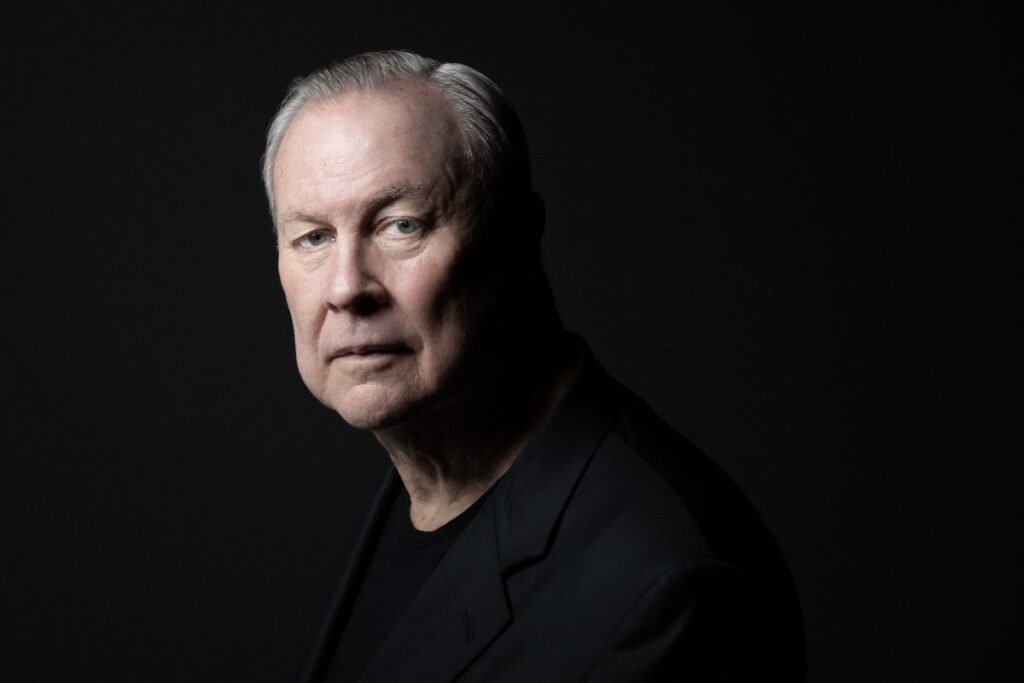

Robert Wilson, Groundbreaking Opera and Theater Visionary, Passes Away at 83

The world of avant-garde theater and opera has lost one of its most daring and imaginative figures. Robert Wilson, the American director, playwright, and visual artist whose work redefined the boundaries of performance art, died peacefully on July 31, 2025, at his home in Water Mill, New York. He was 83.

A statement shared on his official website confirmed the sad news, noting that Wilson passed away after a short but intense illness. Despite his health challenges, he continued working up until the final days of his life—a testament to his enduring passion and creative drive.

Though Wilson’s legacy spans continents and art forms, he held a particularly special place in the hearts of audiences in France. Over the decades, the French embraced him and his artistry like no other country, something Wilson himself acknowledged in a 2021 interview with AFP. He referred to France as the place that truly gave him a home.

Wilson first drew international attention in 1976 with the groundbreaking opera Einstein on the Beach, a collaboration with composer Philip Glass. Clocking in at nearly five hours, the production completely broke with tradition. It lacked a conventional plot, opting instead for a poetic, almost abstract exploration of Albert Einstein’s ideas and the broader concept of space-time. With its hypnotic music, stylized movement, and dreamlike lighting, the opera was more an experience than a story. Audiences were challenged and captivated in equal measure, and the piece went on to become a touchstone in modern performance history.

But Einstein on the Beach was just one chapter in Wilson’s expansive career. His signature style, marked by minimalism, precise choreography, and powerful visual compositions—could be seen in both his original works and his reinterpretations of classic plays and operas. He drew inspiration from a wide range of sources, particularly the theatrical traditions of Asia, and often used silence, light, and physical gestures to say what words could not.

Wilson’s journey into the world of theater started early. Born on October 4, 1941, in Waco, Texas, he was the son of a lawyer and grew up staging his own plays in the family garage by the age of 12. He struggled in school and battled a severe stutter, which was eventually treated through dance therapy—a turning point that would later influence his understanding of the body in performance.

In his twenties, Wilson moved to New York City, hoping to find his place in the art world. Disenchanted by the commercial theater scene he found there, he turned instead to the experimental world of the avant-garde. He connected with visionary figures like Andy Warhol and composer John Cage, as well as choreographers George Balanchine and Martha Graham. These relationships helped him shape a new language for the stage—one that prioritized imagery and emotion over dialogue and narrative.

Wilson’s first major breakthrough in Europe came with Deafman Glance, a largely silent, seven-hour stage piece that debuted at the Nancy Festival in France in 1971. The work was deeply personal, inspired by a real-life encounter he had in 1967. Wilson witnessed a young Black teenager, Raymond Andrews, being assaulted by police. The boy, it turned out, was both deaf and mute. Wilson took the boy under his wing, eventually adopting him, and the encounter helped shape his understanding of non-verbal communication, which became central to his theatrical vision.

Throughout his career, Wilson collaborated with a wide variety of artists across genres. He worked with dancer and choreographer Andy de Groat, actress Isabelle Huppert, and music icon Tom Waits. He even created video portrait art pieces with pop superstar Lady Gaga at the Louvre, and worked with ballet legend Mikhail Baryshnikov. These collaborations highlighted Wilson’s ability to cross artistic boundaries and draw out the essence of performers from all walks of life.

In 1992, Wilson founded the Watermill Center, an interdisciplinary laboratory for the arts located near his New York home. There, he mentored young and emerging artists, providing a space for experimentation and creative exploration. His commitment to nurturing new talent reflected his belief that art should constantly evolve and challenge established norms.

Even as he grew older, Wilson never slowed down. He remained fiercely committed to his work, often juggling multiple productions and projects at once. His death marks the end of an era, but the influence he left behind is undeniable.

His team’s announcement about his passing emphasized his unwavering spirit. “While facing his diagnosis with clear eyes and determination, he still felt compelled to keep working and creating right up until the very end,” the statement read. “His works for the stage, on paper, sculptures and video portraits, as well as The Watermill Center, will endure as Robert Wilson’s artistic legacy.”

Details about memorial services will be announced at a later date, according to his management.

Robert Wilson’s name may forever be linked with avant-garde performance, but he leaves behind more than just groundbreaking shows and art installations. He leaves behind a way of seeing the world—a way that encourages us to slow down, look closer, and think differently. He showed that silence can speak volumes, that stillness can move people, and that art, at its best, can change how we see everything.

Responses